by Jonathan Lorie

Nine million litres of angry river race past my ankles and roar over the cliff. The lip of the world’s greatest waterfall is twenty feet away. I inch a little deeper. Frothing currents rip at my legs as my toes search for a grip. Spray rises a thousand feet in the air. A single slip and I’m gone.

“There is where we swim,” says my guide Eustace, pointing at a circle of black water surrounded by raging surf that’s on the very edge. “There is safe.”

Welcome to the Victoria Falls, adrenaline centre of Africa. Some come here to bungee from the bridge, microlight above the spray, or raft the whitewater that explodes from the gorge three hundred feet below. But I’ve come in search of an older adventurer – the explorer David Livingstone, born 200 years ago, who named these Falls for his Queen. And where better to start than Livingstone Island, perched above his greatest discovery, where I’m about to defy both gravity and sanity by swimming in the Angel’s Pool.

Eustace holds out a hand and I grab it gladly. Together we teeter along a submerged ridge of stones towards a ragged boulder. I scramble over and down the other side, plunging waist-deep into dark water – then deeper – then my feet find a hold and I’m up to my neck but standing firm. I turn around to look.

On every side a torrent of jagged water surges towards the lip. We are five feet from the drop. But the Pool is calm. I stare across the rim of the Falls, where a thousand miles of the Zambezi’s flow are tumbling into space.

I duck my head under water, like a baptism in this wild place, then bob up and grin at Eustace. He throws me a thumbs up. Then we clamber back to the island and safety and lunch.

‘Scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight,’ is how Livingstone described the Falls. And it was from this island that he was the first European to see them, in 1855. Padding back through the reeds, we pass a stone monument to him. Eustace pauses. “Dr Livingstone was very important for us here in Zambia. He opened up this part of Africa for the outside world, for Christianity, and for the fight against the slave trade.”

Livingstone left the island by dugout canoe, but we have Captain Viny and his motorboat – a steel dart that spins a terrifying line parallel to the mile-wide rim and then back up the swirling river. Ten minutes upstream, Viny moors us in smoother waters beside the clipped lawns of the Royal Livingstone Hotel. It’s a splendid white colonial-style place, where zebras wander beneath the trees and tea is served on the verandah.

I duck into the cool of the long bar where ceiling fans whirr and oil paintings portray worthies of Britain’s imperial era. On the wall is a period map of Livingstone’s travels around the Zambezi. It shows lots of blank spaces where nothing was known, and one or two of his geographical errors. A tiny line of type identifies the publisher as ‘Stanfords Geographical Establishment, Charing Cross, London’. Stanfords supplied maps to Livingstone and Cecil Rhodes, and is still the world’s best travel bookshop.

Charming as it is, this colonial stuff was never here in Livingstone’s day. When he tramped through, this was raw bush with a populace ravaged by Arab slavers. The Tonga tribe used the island to sacrifice goats to the gods of the Falls. Colonisation was the remedy the Doctor prescribed for such ills, to bring Christianity and legitimate commerce. We might query such views today, but within 10 years of his death in 1873, the first British settlers had arrived.

Looking for their ghosts, I catch a car into the nearest town – Livingstone, named after the great man, and once the capital of the British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia. It’s a delightfully sleepy place, its main roads lined with stuccoed colonial buildings and gaggles of teenagers. There’s a Stanley House, named after the explorer who found Dr Livingstone starving in the bush, and a David Livingstone Presbyterian Church, and a fast-food joint called the Hungry Lion. But the highlight for me is the town’s museum, which houses a unique collection of his personal possessions.

It’s an odd sensation to stand in front of a glass case that holds the battered white medicine chest with which Dr Livingstone treated the malaria and dysentery that plagued his 30 years of trekking through south-central Africa. Or another that has the flintlock musket that subdued wild animals, hostile tribes and mutinous porters. Here’s his field notebook, open where he has sketched the Falls in navy blue, the spray rising in grey above. There’s a copy of Pilgrim’s Progress, translated into Sechuana for the only convert he ever made, a Bakwain chief called Sechele.

Even closer to the man, here is his wife’s own copy of his first published book, Missionary Travels – the memoir that made him a hero to Victorian England, though Mary was to die of malaria on one of his later expeditions. And there, in front of me, is his hat – the famous blue kepi with its band of gold. Finally, by the door, is a black tin trunk whose lid is stained with blobs of black wax, where every night he fixed a candle to write up his journal. The trunk was by his bed on the morning in the swamps when his African servants found him, hours dead but kneeling in prayer.

Astonishingly, they wrapped the Doctor’s body in tree bark and carried it over 1,000 miles to the coast, where a British warship took it home. But his heart was left in Africa, buried beneath a mpundu tree at the request of the local chief. A piece of the tree is here in the museum.

I drive slowly back to my hotel. Livingstone came here to explore the Zambezi, hoping it would offer a navigable waterway to the heart of Africa. But he was defeated by its rapids. In the end it was trains not boats that opened up the region, starting with Cecil Rhodes’ railway from Cape Town to the great iron bridge that he built at the Falls. By 1904, just 30 years after Livingstone’s death, Thomas Cook was running train trips for tourists to this frontier of empire.

The ultimate in tourism today are the luxury lodges along the banks of the Zambezi. And I am staying in one of the loveliest: Tongabezi. It’s a scattering of glorified African rondavels – round huts with thatched roofs – among tall trees by the water. Inside they are luxurious. Mine has wide windows onto a vast bend of the river, crisp beds under frilly nets, and a claw-foot bath with a view to die for. At night hippos grunt in the shallows as I eat dinner on a raft on the river, the white linen and rare-grilled steak lit only by glittering candles and stars overhead.

It’s a far cry from Livingstone’s experiences. To get closer to his era, I head up-country next day. A rattling 12-seat Cessna flies me to Mfue, gateway to one of Africa’s finest game parks, South Luangwa. We soar above endless tracts of forest without roads or towns, marked only by the brown snakes of big rivers. Driving from the tiny airstrip to the park, I pass fields of maize plants and banana palms, between villages of mud and thatch where families gather in beaten-earth yards and mothers cook over open fires. How much out here has changed?

“David Livingstone crossed the Luangwa River just north of here,” says Adrian Carr, stabbing a finger at the map that spills from his first edition of The Last Journals Of David Livingstone. We’re sitting in his house on the edge of the park and he’s showing me a book from 1874. On its red cover is a gold illustration of porters carrying the Doctor across a swamp. “I know that place. There aren’t any roads up there, but local people still use it to cross the river.”

He pauses, a big, soft-spoken man in khaki shorts and shirt who has spent a lifetime guiding and hunting out here. “You know, life hasn’t changed a lot up there. Sure, they have some schooling, but they still grow what they eat. They still believe in the old gods.

“Can you imagine what it was like when Livingstone came through? The only white man for a thousand miles? He must have been so tough.”

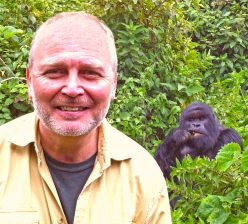

Toughness is a virtue still valued by men like Adrian, one of the last of the great white hunters who made African safaris famous. His father, Norman Carr, invented the walking safari, back in the 1950s, and opened up Zambia for tourism. Black and white photos of the old man grace the walls of Adrian’s game lodge nearby, where I will be staying tonight. They mostly show Norman with two tame lions at his side.

I drive into Kapani Lodge through a gateway roofed with reeds. On the road I have already seen three elephants at a pond. The lodge is built like a colonial estate, or perhaps the kind of mission station that Livingstone dreamed of founding. Its handsome cottages of ochre and thatch face a lake where hippos snort among flowers. Gazelles graze the banks. An open-walled drawing room has horns on the wall and skins on the floor.

I check in my bags and meet my guide, Shadreck Nkhoma, a burly man with a ready smile. We hop in his jeep and roar off to the park. On a bridge across the Luangwa River there are baboons on patrol and a 15 foot crocodile in the water. The park itself is a lovely rolling landscape of tall green grasses and spiky mopane woodlands. A cloud of impalas drift down a slope to a water hole where zebras swish their tails. In a grove of thorn trees, four giraffes stretch up to feed. This is Africa before the modern world. In the distance I hear the coughing of lions.

Rounding a bend, we catch a flash of yellow in a tree. Shadreck hits the brakes. The yellow has black spots. I raise my binoculars and stare into the eyes of a young male leopard. He flexes his paws and glances away.

“My family lived here before it was a park,” says Shadreck as we drive off towards a sunset spot on the banks of the wide river. I ask how far the sense of history goes out here. “I know back to my great-grandfather,” he muses. “His family came from Batoka, towards the Falls. They came to this side of the river and lived the old way – in round mud houses with roofs made of grass, hunting and fishing.” The sunset is a blaze of purple and gold. “Then the park came and they moved out to the village.”

The village is Mfue, and next morning I ask Shadreck to show me around. We wander through the wooden stalls of the market and the concrete cabins of the hardware stores, and then we see a church. “That’s my church,” he beams and ushers me inside.

St Agnes Church is a red brick box with glassless windows and a roof of tin. The elders shake my hand with warmth and surprise. “And this is our teacher, Edwin,” says Shadreck with a grin. Edwin Chupa passes me a bible. I cannot understand its words. “This is in our language,” he smiles, and reads aloud the creation of the world in Nyanja. It’s a lilting, soft language, making the ancient words anew for Africa. His voice rolls round the bare brick walls.

When he stops, I ask what he thinks of the missionaries like David Livingstone who came out here. His old eyes shine. “They brought us the light. They did not know it at the time, but they did. Now we have Christianity, roads, medicines.” He touches my arm. “Because of them, we are standing here now, you and me, understanding one another.”