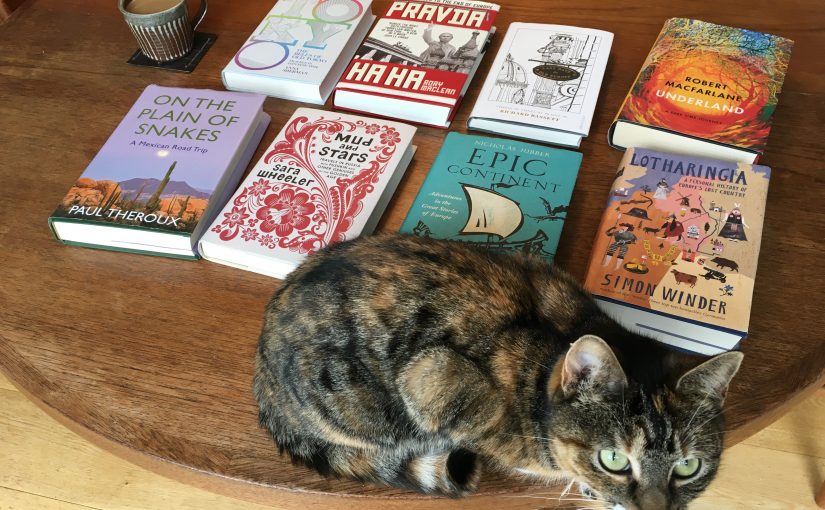

Like Mark Twain, reports of the death of travel writing have been greatly exaggerated. I know this because I’ve spent the winter months reading the best of the past year’s travel books, helped now and then by my cat.

This is not how most people choose to spend their winter evenings, but I’ve been one of the judges of the Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year. It’s the travel world’s annual accolade for its best book writers, our successor to the legendary Thomas Cook Travel Book Award – among whose winners were many giants of our genre, which I fondly recall judging almost 20 years ago.

What a cast of characters the old Thomas Cook had honoured over the years…. Patrick Leigh Fermor, the only writer I know to have joined a cavalry charge across a castle drawbridge during a time of war. Norman Lewis, whose life included spying for Britain, writing the wondrous Voices of the Old Sea, owning a chain of camera stores and living with two women entirely unaware of each other. Then there were dashing English gentlemen like Tim Severin, scintillating heart-throbs like Jason Elliot, Soho bohemians like Jonathan Raban…. The prize judging took place at the Travellers’ Club in Pall Mall, over candlelit dinners on plates decorated with portraits of Lord Byron.

It was a time and a place and a tone. Reports of the death of travel writing have partly been based on the fading of that generation, whose classic style is sometimes described as ‘the white linen suit in the tropics’. That’s an unfair phrase for some of those authors, but reading through this year’s books, it is clear that a sea-change has occurred.

Today the travel books on my coffee table, meekly awaiting judgement, are alive to the modern world and how it is turning. Almost all are reaching across cultures and eras to tell us – and sometimes warn us – about the forces unleashed by our new world disorder. Together they are defining a new territory for travel writing.

In the age of fake news, they offer us the testimony of the traveller, the first-hand report of what is actually going on across our troubled world. As the poet WH Auden once wrote, in a decade not unlike our own: ‘Consider this and in our time.’

So here are some of the shortlist chosen for this year’s award. Quietest of them all was Richard Bassett’s Last Days in Old Europe, whose title says it all. A gentle memoir of living in places that once were part of the glittering Hapsburg empire, it offered a poignant reminder that superpowers can fall apart.

Also seeking lessons from the past was Simon Winder’s Lotharingia, a history of the borderlands between France and Germany since the days of Charlemagne. Was this a travel book? Who knows, but its overriding point was that centuries of conflicts have started there from politicking and nationalism, culminating in two hideous world wars fought along disputed European borders.

The meaning of borders was explored by Paul Theroux, whose book On the Plain of Snakes saw him driving along the US-Mexican border to judge the realities of the controversial ‘wall’ and the societies on either side. Predictably, he found people less divided than their nations, and developed a heartfelt writer’s credo that the heart of a country lies in its ‘hard-up hinterland’ not its flashy tourist sites.

Sara Wheeler traversed the hard-up hinterland of Russia in Mud and Stars, searching for the stories of its great and often exiled writers – people such as Pushkin and Chekov – which mainly reminded me that there was a time when Russia was so cultured that it bothered to send its writers to Siberia. That era persisted from the Tsars through the Soviets, but probably ended with the present regime.

The rise of Putin’s Russia was vividly observed by Rory Maclean in Pravda Ha Ha, in meetings with everyone from illegal migrants to obscenely wealthy oligarchs. In a finely written and funny book, he pursues a serious question: why has Russia moved from optimism and democracy at the fall of the Berlin Wall, towards fatalism and dictatorship today? His answer involves national trauma and the comforts of nostalgia, imagined resentments against the outside world, and a widespread willingness to believe in lies. The implications for our own society are clear and somewhat chilling. Maclean’s book was runner-up for the Dolmen Award – and rightly so.

Moving away from the pressures of our day, but circling back to explain them, were two further books well worth a read.

Epic Continent, by Nicholas Jubber, followed him across the regions spanned by various national myths in Europe – from innocent tales such as the Odyssey in Greece or a Viking saga in Iceland, to stories that have forged influential myths of more questionable kinds: most notably the duplicitous Song of Ronald that fired French patriotism for centuries, and the Rhineland tales of German heroism that inspired Wagner and then the Nazis. The inescapable conclusion is that nations define themselves through myths of a literary kind like these, and also through political myths – or shall we call them lies – about their own greatness, which prompt them towards aggression.

And finally, the winning book was Robert Macfarlane’s Underland, an astonishing work that takes us back to the beginnings of mankind in the rock-art caves of the Dordogne, and forwards to the futuristic mines being built in Finland and America to store our nuclear waste. In between he examines some of the greatest questions – what it means to be human, why we bury our dead, how we treat the world’s resources as riches to be extracted, and ultimately whether we will prove to have been good environmental guardians for the generations that will follow ours. The book may prove to be Macfarlane’s masterpiece.

All of which is a long way from the elegant dinners in the Travellers’ Club of yore. And perhaps all the better for it. I look forward to next year’s list.